Authors

ERM and WBCSD Corporate Performance & Accountability team

Introduction: always model the counterfactual

To compete for capital, sustainability must be framed in the same quantitative language as any other business investment: return, risk and cash flow. This article bridges strategic intent and quantitative execution, demonstrating how sustainability can create and protect value when assessed through established financial metrics.

Sustainability generates value not only through gains achieved but also through losses avoided. Every credible financial case must consider the counterfactual — the “do nothing” path where regulatory, reputational, or operational risks erode performance and impact financial returns over time. For many companies, that erosion takes the form of market share decline due to non-compliance or reputational risk, a rising cost of capital linked to weak ESG standing, or asset impairment from unmitigated climate exposure.

Integrating counterfactual cash flows into project net present value (NPV) calculations — for example, including avoided carbon taxes, compliance costs, or regulatory penalties as part of the investment case — enables sustainability initiatives to be compared directly with any other capital project on the basis of return, risk, and cash-flow performance. To reduce the risk of a subjective view of the counterfactuals, it is important to base key assumptions on externally validated sources such as IEA scenarios, OECD outlooks, or government price forecasts. Referencing well established datasets limits interpretation risk and enhances transparency and credibility – these are vital for business decision making.

Choosing the right financial metrics

Financial metrics translate sustainability outcomes into investor language. They should be selected based on project scope, time horizon, and strategic relevance.

Each measure reveals a different story. IRR supports comparison across competing capital projects. NPV surfaces the strategic upside of risk mitigation, reputation, and resilience that materialise over longer horizons. ROI provides a snapshot for smaller pilots, while payback highlights capital efficiency when short-term recovery is critical.

However, when certain sustainability impacts cannot directly be quantified in monetary terms with confidence, it is better to present them explicitly alongside the financial metrics rather than embedding them into cash flows. This keeps the financial case grounded in measurable inputs while ensuring that strategic benefits are still part of the decision. When decisions involve multiple non-financial considerations, a multi criteria view can help make those trade-offs visible and avoids overstating certainty.

| Metric | Ideal Use Case | What It Captures Best | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | Discrete, capital-intensive projects with clear start and end points (e.g., plant retrofits, renewable installations) | Relative profitability and efficiency of capital deployment | Can overstate attractiveness for projects with irregular cash flows or long tails, no differentiation on size of project |

Net Present Value (NPV) | Strategic or enterprise-level initiatives that influence long-term competitiveness and resilience (e.g., net-zero transition plans, renewable transitions) | Total value created (or lost), incorporating both time value of money and risk through the discount rate (weighted average cost of capital – WACC) | Requires robust forecasting and assumptions on growth and terminal value. NPV may undervalue projects with strategic, non-financial benefits if these are not monetised in the cash flow forecast. |

| Return on Investment (ROI) | Tactical or short-cycle initiatives such as efficiency upgrades or targeted operational improvements | Simple and intuitive comparison of benefits versus costs | Does not take into account timing of cash flows and long-term value effects |

| Payback Period | Liquidity-focused decisions or projects prioritising rapid capital recovery (e.g., energy-saving retrofits under tight budgets) | Speed of cash recovery and risk mitigation in the near term | Disregards post-payback cash flows and strategic benefits |

Each measure reveals a different story. IRR supports comparison across competing capital projects. NPV surfaces the strategic upside of risk mitigation, reputation, and resilience that materialise over longer horizons. ROI provides a snapshot for smaller pilots, while payback highlights capital efficiency when short-term recovery is critical.

However, when certain sustainability impacts cannot directly be quantified in monetary terms with confidence, it is better to present them explicitly alongside the financial metrics rather than embedding them into cash flows. This keeps the financial case grounded in measurable inputs while ensuring that strategic benefits are still part of the decision. When decisions involve multiple non-financial considerations, a multi criteria view can help make those trade-offs visible and avoids overstating certainty.

Table 1: Illustrative Financial Performance of Selected Sustainability Projects

(Figures are indicative and based on publicly available data. Actual project economics vary by context, geography, and energy costs.)

| Initiative | Description | Capex (£) | Annual Savings (£) | NPV (£) (8% WACC) | IRR | Simple Payback (yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. . Solar Energy Installation | 50 kW rooftop solar retrofit replacing grid electricity | £68,250 (50kW x £1365 1) | £11,280* | £42,504 | 15.6% | 6.05 |

| 2. LED Lighting Upgrade | Replace CFL lamps with LED panels in a 1000 m2 commercial facility | 10 2(£/m2)× 1000 = £10,000 | £2,514* | £4,447 | 18.8% | 3.98 |

| 3. Electric Vehicle Fleet Transition | Replace 20 diesel vans with electric equivalents, incl. depot chargers | £191,440* | £1,500 per van 3 × 20 = £30,000 | £9,862 | 9.1% | 6.38 |

*Notes on calculations (table 1)

1. Solar panel savings calculation (Avoided costs): [System capacity (kW) × Yield (kWh/kWP/year) × Electricity price (£/kWh)] – [Capacity (kW) × O&M costs/ (£/kW)] = (50 × 900 × 0.2629 ) -(50 × 11 )

2. LED light replacement savings calculation: Lighting requirement/m^2 ×((1÷Lumens/ W before retrofit)-(1÷Lumens/ W after retrofit))× Lighting hours per year×0.001×Electricity cost (£/kWh)×Area of property replaced (m^2) = 500 ×((1÷57 )-(1÷100 ))×(10×5×51)×0.001×0.2629×1000

3. EV incremental Capex: [(Cost of purchasing an EV van)-(Cost of purchasing a diesel van)+Investment in charging infrastructure = (65,999 – 61,427 +100,000)

Notes on Assumptions:

Solar panel installation: Savings have been estimated using an avoided-cost method, which compares a counterfactual scenario where electricity continues to be purchased from the grid versus one where on-site solar power offsets part of that consumption. The analysis therefore captures the annual cost avoided through self-generation rather than energy procurement. The useful life has been assumed to be 20 years. No export revenue or tax incentive has been included, making the results conservative.

LED lighting: The savings estimate is based on a counterfactual lighting scenario in which the facility continues to operate using compact fluorescent lamp (CFL) bulbs at their current energy consumption and efficiency. The analysis assumes a lamp-only replacement (no new fittings required) and excludes the counterfactual cost of CFL replacement, meaning the full purchase cost of the (light-emitting diodes LED lamps is treated as new capital expenditure. An optimistic unit cost of £10 per lamp has been used. The useful life has been assumed to be 8 years. If higher LED unit prices were included, the project’s NPV and IRR would be lower.

Fleet electrification: Annual savings were derived by comparing a counterfactual diesel fleet scenario (fuel costs) with an equivalent fleet of electric vehicles. We are assuming that the entire fleet is replaced in one go, not phased over time. Government incentives, such as the Plug-in Van Grant (£2,500–£5,000 per vehicle) , are not included in this base case. The useful life has been assumed to be 10 years. If these rebates were included, they would lower the total capex and result in a higher NPV and IRR.

Market Forces That Shape Long-Term Value

The case studies above focus on direct operational impacts, but long-term market forces, such as carbon pricing, can materially strengthen the financial case for sustainability investments. As carbon markets tighten as demand for carbon credits and allowances increase, avoided emissions translate into increasing economic value, raising the NPV and IRR of projects like solar PV, lighting upgrades, and fleet electrification. To address concerns around carbon price uncertainty, it may be useful to show how results behave under different scenarios or conservative price bands. This helps demonstrate that the investment case is not dependent on a single policy or price path.

Carbon pricing also affects value chains. Suppliers exposed to rising carbon costs may pass these through as higher input prices, while customers, especially in business-to-business markets, are shifting towards lower-carbon products. Including these dynamics in “with” and “without” scenarios helps show how investments like solar PV, LED retrofits, fleet electrification, or circular packaging not only reduce operating costs but also protect demand, margin, and long-term enterprise value.

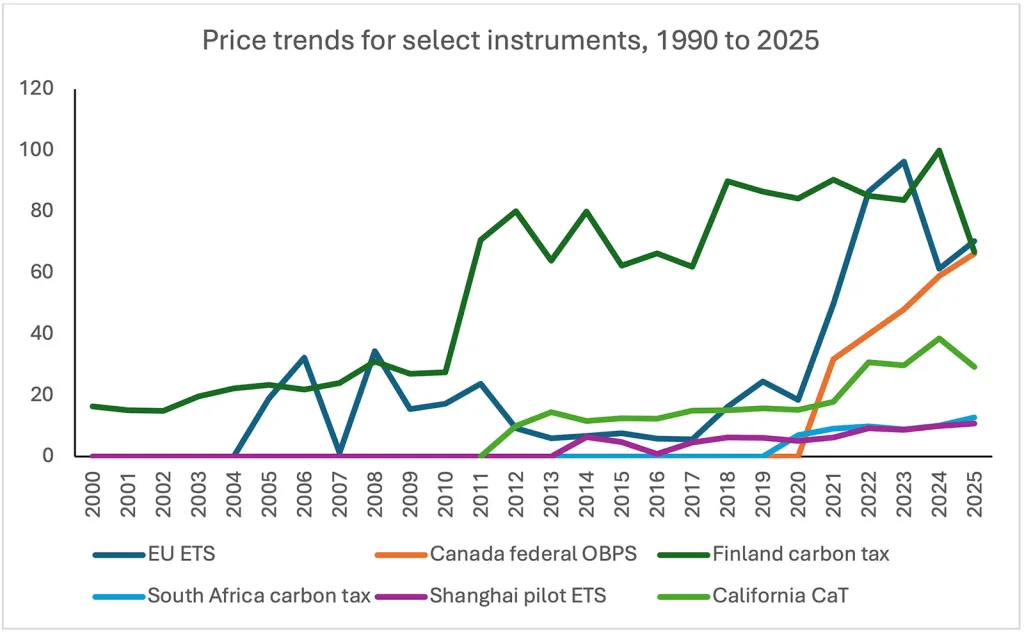

Compliance carbon markets continue to mature globally, and price signals are strengthening across both advanced and emerging systems. Long-term price signals from mature markets can be used as anchors when assessing future exposure, while still allowing for uncertainty through ranges rather than single price points. This reduces dependence on any single forecast and supports a more balanced view of risks and opportunities. Figure 1 below illustrates this trend, showing how established markets such as the EU ETS and California’s cap-and-trade program have moved onto a clear upward trajectory. At the same time, developing systems such as South Africa’s carbon tax and the Shanghai pilot ETS are beginning to introduce more explicit pricing of emissions.

Case Studies

For example, WBCSD member Ørsted pivoted from fossil-based generation to offshore wind. Ørsted management, framed the transition not as a moral imperative, but as a portfolio reallocation with clear financial metrics and target for growth. Early wind projects produced lower IRRs than legacy assets, but higher growth and more predictable forecasted FCF and lower long-term WACC. By explicitly modelling avoidance of losses attributed to stranded-assets (legacy O&G activities) and access to lower financing costs, Ørsted has demonstrated superior risk-adjusted returns. From 2016 to 2021, its market capitalization quadrupled, validating that sustainable transformation can outperform when appraised through robust financial lenses.5

WBCSD member DSM-Firmenich applies IRR and FCF modeling, embedding avoided carbon costs, future compliance savings, and consumer-premium effects into its investment appraisals. DSM’s “Sustainable Portfolio Steering” tool enables it to align innovation pipeline decisions with sustainability impact and financial value creation. This discipline allows the company to prioritize R&D spending where sustainability advantages correlate directly with economic value added.6

On the other hand, in early 2025 BP announced a strategic reset, cutting low-carbon investments by over US$5 billion and increasing oil and gas spending to about US$10 billion as it shifted back toward higher-margin fossil projects. This demonstrates how transitions can underperform when assumptions around policy, costs or market conditions continue to evolve and are not fixed, reinforcing the need to model upside and downside with equal discipline.7

In practice, combining metrics yields the richest insights. A decarbonization retrofit may show a modest IRR when modelled in isolation, but strong and positive FCF once evolving avoided carbon-price exposure is included. A quick-payback efficiency upgrade can further enhance enterprise value by lowering long-term volatility and demonstrating credible progress to investors. What matters is that sustainability projects are judged through the same multi-lens rigor as any other investment.

Integrating dependencies into cash flow models

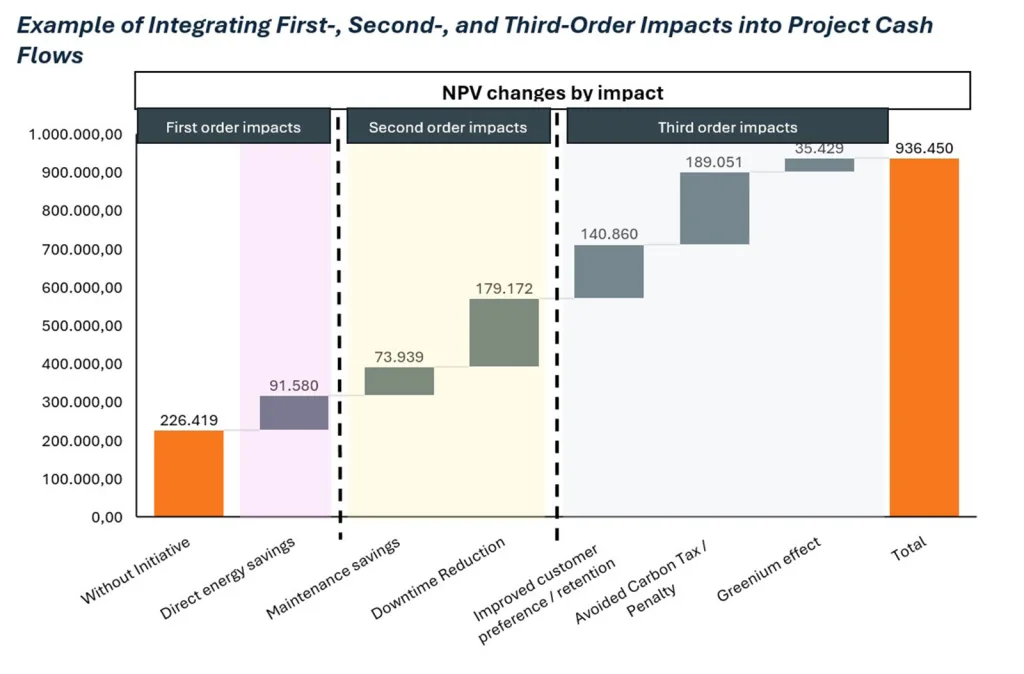

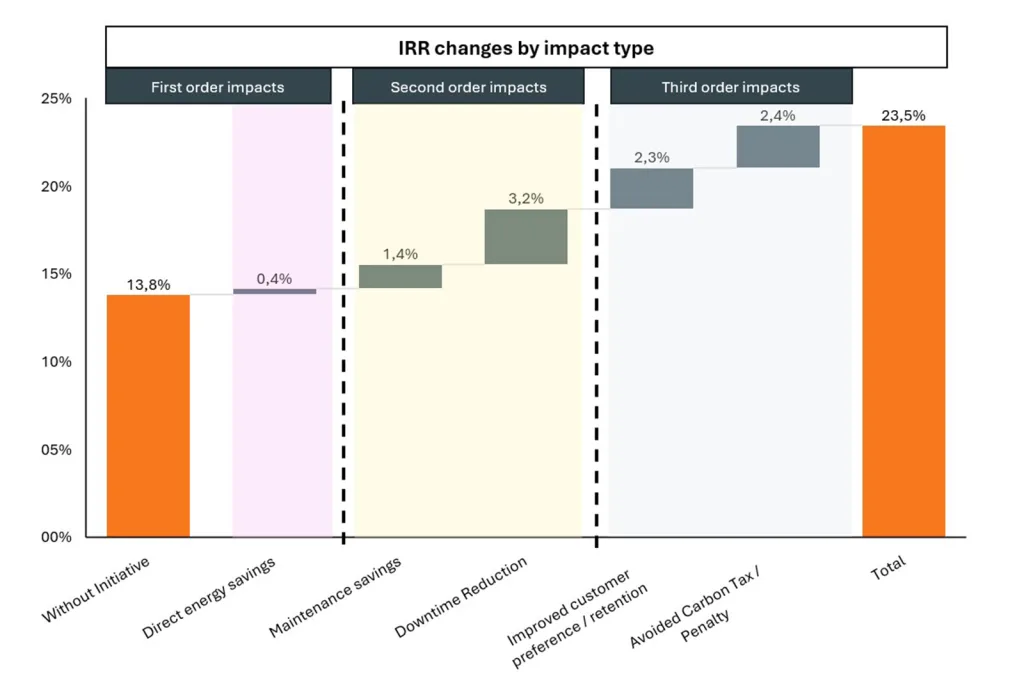

As explored in our earlier article, Financial quantification: leveraging the interdependencies of sustainable investments, sustainability actions rarely operate in isolation. Their effects propagate through operations, supply chains, and markets — influencing revenues, margins, and risk profiles.

First-order impacts such as energy or material efficiency are easily measured, but second- and third-order effects — supplier stability, brand strength, customer retention — also shape free cash flow and the firm’s cost of capital. Building these interdependencies into “with” and “without” scenarios ensures that IRR, FCF, and other valuation metrics reflect the true enterprise value of sustainability initiatives, not just their direct savings.

Example of Integrating First-, Second-, and Third-Order Impacts into Project Cash Flows

Note: Since the example represents a discrete project with a defined 5-year life, no terminal value is applied. For enterprise-level transitions or ongoing decarbonisation programmes, a terminal value would typically be included to reflect continuing benefits and long-term competitiveness.

| Category | Assumption | Description / Rationale | Example: Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project Context | Project Type | Sustainability retrofit (e.g., energy efficiency upgrade) | |

| Project Life | Duration of forecast period | 5 years | |

| Initial Investment (Capex) | Upfront cost of implementation | €2,000,000 (€1,500,000 without retrofit) | |

| Base WACC | Company’s weighted average cost of capital | 8.0% | |

Baseline (Without Initiative) | Annual Operating Savings | None – continued high energy and maintenance costs | |

| Carbon Tax / Compliance Costs | Expected cost under BAU (business-as-usual) | €300,000 in Year 5 | |

| Revenue in year 1 | €400,000 | ||

| Revenue Growth | Nominal improvement in market position | €20,000 per year | |

| First-Order (Direct Operational Efficiency) | Energy Savings | Reduced energy expenditure due to retrofit | +€150,000 per year |

| Second-Order (Resilience & Reliability) | Maintenance Savings | Minor operational improvement | +€20,000 per year |

| Downtime Reduction | Improved uptime and fewer production disruptions | +€30,000 – €70,000 per year | |

| Third-Order (Market & Financial Effects) | Revenue Uplift | Improved customer preference / retention | +€20,000–€70,000 per year |

| Cost of Capital (WACC) Reduction | Increased investor confidence (Greenium effect) | -0.4% (from 8.0% → 7.6%) | |

Avoided Carbon Tax / Penalty | Counterfactual benefit added to terminal year | +€300,000 |

Building a structured framework for decision making

A disciplined decision process combines counterfactual thinking, integrated dependencies, and the right financial lenses. Four steps make the approach repeatable:

- Define the counterfactual baseline: Define the financial cost of inaction — capital replacement cycles, lost market share, rising cost of capital, stranded assets, or non-compliance penalties. Strengthening data governance at this stage helps improve the reliability of assumptions used in both the counterfactual and project scenarios. Clear documentation of input sources, independent review of key data points, and alignment with leading frameworks such as ISSB S1 and ISSB S2 support more consistent and comparable modelling across different investment cases.

- Quantify direct and indirect cash flow impacts: Map first-, second-, and third-order effects into cash-flow assumptions.

- Select the right metrics for project type and horizon: Match IRR, FCF, ROI, or payback to project type and horizon; use multiple views to capture both near- and long-term value.

- Run scenario and sensitivity analysis: Stress-test for carbon-price trajectories, policy shifts, and market volatility to assess robustness.

Following this structure allows sustainability investments to be compared directly with other capital allocations, using consistent, financially credible criteria.

Conclusion: embedding value thinking in sustainability

Embedding sustainability within return- and cash-flow-based methods enables it to compete on equal footing with any other capital decision. Quantification translates purpose into financial performance, allowing CFOs and CSOs to prioritise initiatives based on impact on enterprise value, not narrative appeal.

When modelled through a commercial lens and fulsome assessment of financial the metrics, sustainability initiatives can become part of a disciplined portfolio built on measurable returns. The final article in this series seeks to close the loop and the evidence of this credible and proven sustainability value creation.

For an overview of this series in the context of WBCSD and ERM’s collaboration on quantifying sustainability for corporate finance, see here.

- GOV.UK, 2025. Solar PV Cost Data (MCS Installations). [online dataset] Updated 29 May 2025. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/solar-pv-cost-data ↩︎

- UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), 2024. Retrofitting Office Buildings: Building the Case for Net Zero. [online report] Available at: https://ukgbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Retrofitting-Office-Buildings-Building-the-Case-for-Net-Zero.pdf ↩︎

- Renewable Energy Association & Energy Saving Trust, 2024. Electrifying the Fleet. [online report] Available at: https://www.r-e-a.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Electrifying-the-Fleet-REA_and_EST-August2024.pdf ↩︎

- World Bank Group, 2025. Carbon Pricing Dashboard – Compliance Carbon Prices. [online dataset] Available at: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/price ↩︎

- Ørsted Group. (2023). Annual Report 2023: Our Transformation to Green Energy. Retrieved at: https://orsted.com/en/investors/ir-material ↩︎

- DSM-Firmenich. (2024). Integrated Annual Report 2024 – Our Approach to Sustainability. Retrieved at: https://annualreport.dsm-firmenich.com/2024/sustainability/our-approach-to-sustainability.html ↩︎

- BP plc. (2025). BP ramps up oil and gas spending to $10 billion. Retrieved at:

https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/bp-ramps-up-oil-gas-spending-10-billion-ceo-rebuilds-confidence-2025-02-26/ ↩︎

Outline