Authors

Jenny Kwan (WBCSD), Inês Amorim (WBCSD), Vignesh Gowrishankar (BCG), Elfrun von Koeller (BCG), Anastasia Kouvela (BCG), Lizzy Coad (BCG)

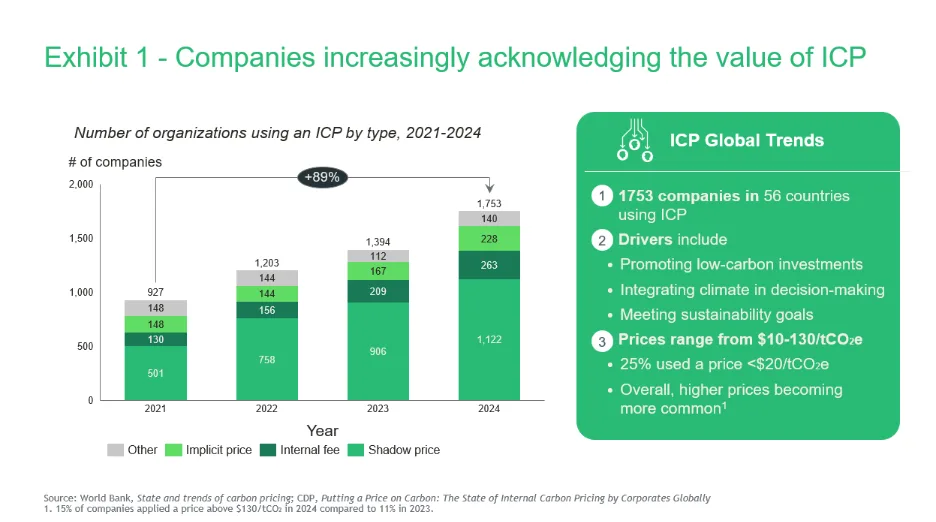

1753

companies in 56 countries are using internal carbon pricing (ICP) in 2024

+89%

increase in organizations using ICP from 2021 to 2024

14%

of companies reporting to CDP use ICP; they are 3.5 times more likely to have climate requirements in supplier contracts

A shadow carbon price is used only to guide investment decisions and isn’t charged to the P&L, so it’s often seen as ‘not real money.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

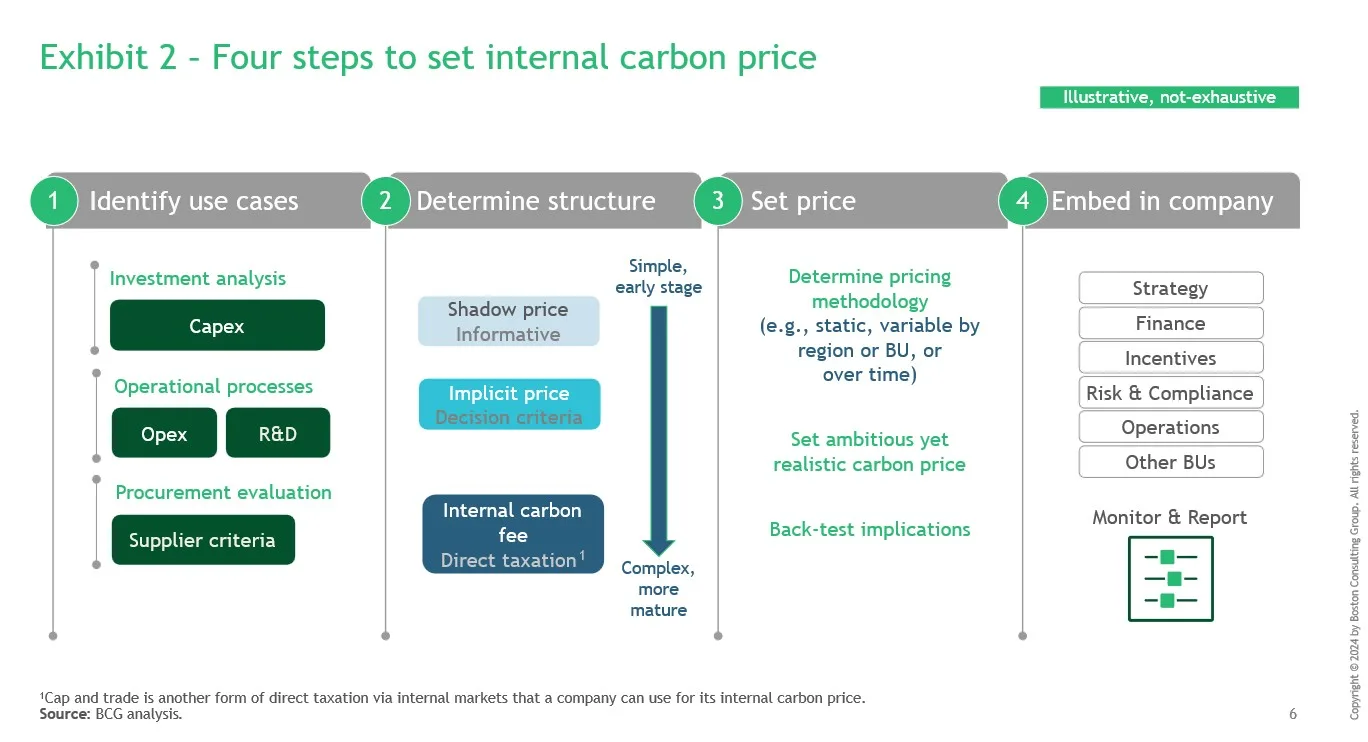

As discussed in Integrating climate with financials, embedding climate into corporate financial processes is no longer a nice-to-have but often a critical unlock. One tactical approach is Internal Carbon Price (ICP), a cost per unit of CO2 emissions usually voluntarily set by a company. ICPs can take various forms, which we define for the purposes of this article as follows:

- Shadow price1 (to build awareness): A notional cost assigned to emissions to raise awareness and loosely guide decision-making without direct financial impact.

- Implicit price (a decision criterion): The cost of carbon is embedded in operational or investment decisions and used as a criterion to evaluate investments and trade-offs.

- Internal fee (with direct financial implications for business units [BUs]): A direct charge applied to BUs for their emissions, creating financial consequences to incentivize emission reductions.

ICPs have gained increasing traction on corporate agendas, with more than 1.5 times the number of companies using them in 2022 compared with 2015 (see Exhibit 1).

WBCSD Member Insights

The closer a company can get to translating emissions into real dollars, the more effective the tool will be: “Being able to speak dollars instead of emissions helps drive home to employees the real implications of climate.”

Despite its power as a tool to integrate climate with financials, however, ICPs remain underutilized. Based on recent analyses, 14-18% of companies use an ICP. Of companies with a price, roughly two-thirds had a shadow price, which while helpful in raising awareness of carbon implications, may stop short of affecting corporate decisions.

Even companies with ICPs speak of ongoing challenges, including securing buy-in because ICPs are not perceived as “real money”; fairness concerns for high-emitting BUs; and uncertainty around evolving a static or uniform ICP to reflect the idiosyncrasies of different divisions or geographies over time.

Given these challenges, we have identified five key unlocks for companies looking to establish or refine their ICP schemes: starting with a shadow or implicit price to integrate financial and sustainability decision-making; leveraging external inputs to inform price setting; tailoring ICPs to business units, regions, or operations for greater impact; leveraging performance metrics and financial incentives to gain buy-in; and exploring carbon budgets as a flexible, complementary tool.

Use Internal Carbon Pricing to integrate financial and sustainability decision-making

ICPs have multiple use-cases for integrating financial and sustainability decision-making, often linked to the type of price used (see Exhibit 2):

- Investment analysis: A shadow or implicit price is applied to carbon over the investment life cycle, then considered or used as a decision criterion in valuations to account for climate-related risks and emissions costs.

- Operational processes: An internal carbon fee is applied to annual emissions of BU operations, then charged as opex to individual BUs, reinforcing sustainability targets.

- Procurement evaluation: A shadow or implicit price is applied to embedded carbon associated with suppliers’ products or services, then considered or used as a decision criterion in procurement bids.

As a starting point, companies often begin with a shadow price to build awareness about carbon, which can then evolve into implicit prices, for example for capex. The recently published SPP Carbon Pricing Principles set out a practical framework for companies to integrate internal carbon pricing into procurement, aiming to drive decarbonization across supply chains by embedding transparency, consistency, and climate ambition into tendering and supplier engagement. We see increasing interest from companies in exploring options along these lines. Finally, companies can consider internal carbon fees to generate proceeds to fund decarbonization. Bayer, Novartis, Nestlé, and H&M all incorporate ICPs utilizing various combinations of these different approaches.

Blueprints for Success

Microsoft uses fees on Scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions to fund renewable energy, offsets, technology innovation, and internal emissions reduction and energy-efficiency projects. BUs can track their emissions and the evolution of their fee in real time throughout the year. Management regularly holds discussions about ICP usage with finance and BUs to ensure that implementation accounts for BU-specific context while aligning with overall strategy.

For companies hesitant to implement internal fees as such, proxies where buy-in already exists can be a practical approach. A global consumer goods company, for example, purchases renewable energy certificates (RECs). The cost of this green power purchase is internally charged back to global sites in proportion to their Scopes 1 and 2 emissions, with the proceeds reinvested in renewable energy projects.

Leverage inputs to inform Internal Carbon Price setting

Once a company decides on price structure and use cases for ICPs, the next step is price setting (see Exhibit 2). ICP levels can be shaped by factors including regulations (for example, carbon taxes), carbon offset prices, and abatement costs for emissions reduction technologies informed by marginal abatement cost curves (MACCs; see the first article in this series, “Weaving climate considerations into corporate operations”).

Prices can vary widely across companies: they can range from $10 to $130 per metric ton of CO₂e, with a quarter of companies applying a price below $20 and a median price of $49/ton across all companies using an ICP. In 2024, 15% of companies set an internal carbon price above USD 130 per tCO₂e, up from 11% the previous year, showing that higher prices are becoming increasingly common. Regular reviews and robust data systems are essential to align with evolving regulations, emissions performance, and targets.

ICP buy-in is generally easier in regulated carbon markets and for brands or BUs with strong public sustainability commitments. In regulated carbon markets, mandatory requirements drive the internalization of carbon costs. For example, an environmental services provider shared that it implemented its ICP primarily as a response to the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). In the case of brands with strong sustainability goals, stakeholders are already primed to be more receptive to ICPs.

“Establishing Internal Carbon Prices isn’t the problem. It’s convincing leaders that it’s a fair price.”

– Challenges identified by practitioners

Tailor Internal Carbon Price design to maximize effectiveness

An IT company raised concerns about the administrative burden of implementing ICPs across a large multinational. Unsurprisingly, many companies begin with a flat ICP. Over time, to enhance its effectiveness, companies can consider gradually tailoring the price structure, use case, and price level to reflect the specific realities of different BUs, regions, or operation types. Some approaches for tailoring ICPs include:

- By BU: An industrial goods company previously set a flat ICP using abatement technology-informed average price of decarbonization and peer benchmarks. Now, it plans to tailor ICPs for each BU, considering market conditions and technological maturity of available levers (for example, abatement levers for mining and chemicals differ, each with its own associated abatement costs).

- By region: A heavy industrial company is tailoring its ICPs by location—higher in developed markets and lower in emerging ones—based on nationally determined contributions and carbon regulations. Broadly, many companies apply higher ICPs in regulated markets like the EU ETS or limit ICPs to those regions.

- By BU and region: A multinational conglomerate is rethinking its one-size-fits-all ICP due to regional and product differences. It plans to explore a matrix of ICPs by BU and region. The company will also hold one-on-one discussions with high-emitting BUs to address concerns and explore supplemental measures.

- By operation type: Some companies adapt the emission scope coverage of their ICPs depending on the nature of their operations. A business that procures more raw materials, for example, may have a higher share of Scope 3 emissions than a service-oriented company, and therefore might consider varying its ICPs approach for Scope 3.

WBCSD Member Insights

“Culture starts at the top. If executives show that they’re fully behind the ICP plan, it’s much more likely for other company leaders to get on board.”

Enhance buy-in for Internal Carbon Pricing through metrics and incentives

Carbon fees can often be perceived as punitive taxes, with the benefits being challenging to justify to teams. To encourage Internal Carbon Pricing adoption, some companies combine them with performance metrics and monetary incentives, such as budgetary rewards for BUs (departments).

Establishing effective incentives is not always straightforward, however. Several company leaders have reported mixed results. For example, a fragrance and beauty company proposed linking bonuses to emissions reductions but faced resistance, particularly from creative teams, who viewed it as an additional constraint on their operations.

Broadly, to enhance buy-in, companies can consider the following:

- Educating employees on the financial value of sustainability. Some companies find that adopting more sustainable practices yields financial benefits, even in the short term. Mahindra & Mahindra, for instance, invested in a range of measures to improve energy efficiency in its factories, such as replacing conventional lighting with LED bulbs and installing solar water heaters. Because of the savings they enabled, these changes had a payback period of only 1.2 years, demonstrating to employees that sustainability could go hand in hand with fiscal responsibility. Increasingly, executives are signaling to employees that longer-term investments are integral to future value creation, as highlighted in a 2024 report from the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing.

- Involving BUs in setting decarbonization goals and ICPs, ensuring clarity on how each BU can contribute, and determining a reasonable ICP for each.

- Starting with uncontroversial analogues for buy-in. For example, the cost of high-quality renewable energy certificates could be used as a proxy for an ICP.

- Accepting that full buy-in, even with incentives, isn’t always possible. Companies can instead pick a reasonable starting point and refine as needed over time.

Explore carbon budgets as an alternative or add-on to Internal Carbon Pricing

In some cases, ICPs may not be maximally feasible or effective for a company or specific BUs. Carbon budgeting can serve as an alternative or add-on to ICPs. Based on a company’s net zero pathway, corporate emissions targets can be divided into time-based carbon budgets, similar to financial budgets, which can then be allocated to specific BUs and/or activities. This approach offers several advantages:

- Creates accountability for emissions across all levels.

- Sets measurable performance targets to ensure the company is on track to meet sustainability commitments.

- Allows multiyear flexibility, requiring emissions exceedances to be offset by future reductions.

- Encourages buy-in and adoption by integrating carbon management into BUs’ processes similar to traditional financial budgeting.

- Avoids concerns about the equivalence of carbon emissions and financial dollars (for example, price on carbon not being “real money”).

WBCSD Member Insights

A service and utility provider that has used ICPs for nearly a decade but was unsure how to evolve its carbon price recently adopted carbon budgets as a complementary tool. The company engaged all BUs to analyze and educate them on its net zero trajectory. Carbon budgets were then set for each business unit’s Scopes 1 and 2 emissions, which comprise more than half of the total company footprint. These budgets were not monetized, simplifying understanding and implementation.

No-regret foundational moves

- Educate teams on financial value of sustainability. Through internal communications and trainings, educate leadership and employees that carbon does indeed involve “real money,” especially in regions with regulated carbon markets, to pave the way for ICP buy-in.

- For companies looking to establish ICPs, explore inputs for price setting. Review potential price-setting inputs (carbon taxes, abatement-technology-informed abatement costs, etc.) and peer benchmarks to gauge starting points for setting ICPs.

- For companies looking to evolve ICPs, evaluate opportunities for tailoring ICP approach. Consider how the current ICP is received by different BUs and regions, and facilitate internal discussions to explore opportunities for further customization.

- There is often a blurred line between using shadow prices for awareness and implicit prices for decision-making. Companies frequently use these terms interchangeably, with “shadow price” being more common. ↩︎

Outline