Authors

Jenny Kwan (WBCSD), Inês Amorim (WBCSD), Vignesh Gowrishankar (BCG), Elfrun von Koeller (BCG), Anastasia Kouvela (BCG), Hardik Sheth (BCG)

3/4

of the largest companies globally now report sustainability information with financial disclosures in annual or integrated reports, and roughly 85% of them use double materiality, or both economic and other factors

90%

of companies surveyed by BCG report financial gains from decarbonization

We’re ahead of the curve on sustainability, but I’m not sure if we’ve tied it as strongly to financials as we should have or have unlocked all the value opportunities there.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

Sustainability and finance teams often struggle to collaborate for several reasons: the lack of a common language to translate climate-related risks into financial impact; the market undervaluation of sustainability; and the inherent financial characteristics of climate initiatives (longer payback periods, harder-to-quantify ROIs, etc.), which are at odds with preferred business metrics and priorities.

Embedding climate considerations into financial processes is no longer a nice-to-have. To ensure long-term competitiveness, companies can act now to align value creation and risk mitigation with both business and sustainability goals.

This article explores five key unlocks in integrating climate with financials:

- Adding climate as an overlay to financial planning

- Embedding financial implications of climate into corporate budgeting

- Evaluating decarbonization cost sharing between the company and upstream/downstream actors

- Considering “cost of inaction” to enhance business case…

- … while seeking “rewards of action” as the prize

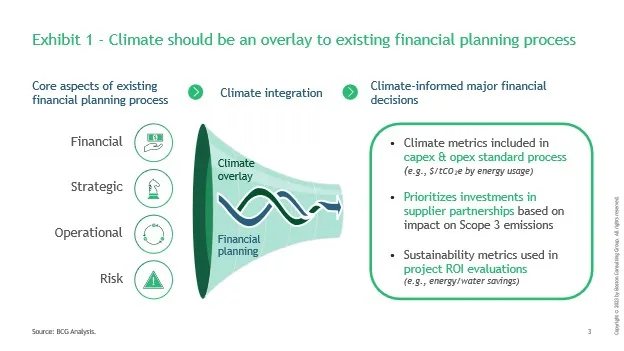

Add climate as an overlay to financial planning

Balancing cost-effective delivery with clear prioritization is tough when faced with high costs, expensive technological investments, and the need to spend strategically—some investments now versus larger ones later.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

Climate considerations cannot be treated as stand-alone or parallel to financials but rather be deeply integrated in core business case elements, including strategic benefit, financial impact, operational feasibility, and risk profile (see Exhibit 1).

Such a climate overlay calls for governance and process modifications along four dimensions:

- Whom to involve: Establish leadership accountability and foster a sustainability-focused culture with cross-functional teams from, for example, finance, sustainability, operations, and procurement.

- What to assess: Prioritize most material sustainability issues, considering the entire product life cycle and value chain.

- How to assess: Evaluate value and costs both internally for the business and externally for society.

- How to decide: Adjust decision rules by adding sustainability criteria to internal rate of return (IRR) and net present value hurdles.

A common challenge is misalignment between regular financial and climate timelines. While typical projects’ financial payback materialize within a few years, sustainability projects often take longer to deliver their full potential, although there are increasing indications of shorter-term paybacks, notably in energy, water and waste. An environmental services provider noted that ten-year client contracts make it hard to justify long-term climate investments where benefits extend beyond the contract term.

Systemic issues, like the free-rider problem and misaligned incentives, make it harder to sustain momentum on climate initiatives that demand shared responsibility.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

Even among climate initiatives, payback timelines are not always aligned. Manufacturing companies noted that climate initiatives tied to 2025 or 2030 goals are often prioritized. Consequently, emissions reduction efforts with immediate, measurable outcomes tend to take precedence over long-term resiliency investments with delayed value.

WBCSD Member Insights

During due diligence for acquisitions, a food and beverage company plans to evaluate how targets align with financial and sustainability objectives. As a representative noted, “If we acquire something to win market share or increase revenue, but it delays our progress toward our net zero goals, it becomes a disjointed initiative.“

Companies are experimenting with several approaches to tackle misaligned timelines:

- Elevating sustainability criteria to be on par with financial criteria via tools such as internal carbon price (deep dive to follow in the next article in this series) or extended payback periods, making sustainability-driven projects more financially attractive.

- Adjusting financial payback thresholds for projects with significant sustainability benefits. This is sometimes necessary to shift corporate mindset. For example, an industrial company discovered that employees were self-censoring climate initiatives due to a rigid focus on meeting IRR targets. Lower-level staff assumed most climate initiatives would be rejected, so they did not propose potentially successful ideas.

- Encouraging teams to find creative solutions earlier in the project life cycle to align sustainability projects with standard financial metrics.

Blueprints for Success

As noted in Accounting for Sustainability’s Essential Guide to Capex, Marks & Spencer engaged a cross-functional team of architects, engineers, and procurement experts early in the design of sustainable stores. Both sustainability and commercial viability were core design drivers, and the projects were approved via standard financial hurdles.

Embed financial implications of climate into corporate budgeting

To fully integrate the financial implications of climate into operations, companies can translate them into the standard corporate budget, ideally through three elements:

- Capex: Climate-related capital expenditures and R&D, while accounting for avoided capex such as avoided capital replacement or reduced risk of damage from hardening. Amounts can be estimated using cost proposals provided by developers or vendors.

- Opex: Climate-related operational expenditures, as well as any staffing or capabilities needed for sustainability initiatives, while accounting for potential savings (for example, resource and energy efficiencies or business growth opportunities from low-carbon transition).

- Cost of inaction: Mounting future costs and missed opportunities due to delayed climate action.

On the back end, integrating climate into corporate budgeting requires robust data and IT infrastructure to collect and merge hitherto disparate datasets, and generate actionable insights.

Evaluate decarbonization cost sharing with upstream and downstream actors

While climate-financial integration is more manageable for Scopes 1 and 2 emissions, Scope 3, which covers the broader supply chain, remains a somewhat uncharted frontier. A fragrance and beauty company is grappling with how to share financial and carbon value and costs between itself, suppliers, and customers. “Customers want greener options, but not at a premium,” a multinational conglomerate noted.

Our discussions with companies surfaced three key considerations regarding how decarbonization costs may be split between these actors:

- Explore a spectrum of cost-sharing options. Passing climate costs on to suppliers or customers can be a spectrum. On one end, some ambitious companies bear most of the costs of switching to sustainable inputs, or even help suppliers access and purchase renewable energy. On the other end, some companies apply pressure on suppliers to reduce costs. Each company can decide where it falls on this spectrum based on its strategy, climate ambition level, level of influence, and place in the value chain, among other factors. Additionally, companies—suppliers and buyers alike—can explore sustainable supply chain finance solutions, which help suppliers access much-needed capital as well as save on financing costs for the collective net zero transition.

- Adapt financial models to changing conditions. Supplier decarbonization efforts and green premium feasibility are constantly evolving. Companies can develop flexible financial models and assess how different scenarios affect project returns.

- Unlock tangible savings. Companies can proactively identify savings opportunities and work with relevant internal stakeholders to ensure that these savings are demonstrated over time.

Consider “cost of inaction” to enhance business case

The market often undervalues climate action, and we lack a common language to translate its financial impact, making it hard to justify long-term initiatives with longer payback periods and uncertain ROIs.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

A key takeaway that resonated strongly with companies is that quantifying the cost of inaction can create a sense of urgency and strengthen the business case for sustainability. When doing so, companies may consider climate impacts from both macro perspectives (harsher climate, carbon regulations, etc.) and company-specific cost drivers if no action were taken.

WBCSD Member Insights

Properly quantifying the cost of inaction is pivotal in creating urgency and buy-in. When presented with the tangible risks—like potential revenue losses from climate disruptions or regulatory costs—leaders see sustainability as a business imperative, not just an ethical choice.

The cost-of-inaction argument may be more persuasive for certain types of companies:

- Companies with longer-term contracts are more likely to experience the impact of inaction within the contract period, making immediate action more urgent.

- Companies that extensively leverage external climate financing mechanisms could find delaying action makes it increasingly difficult to secure funding from climate-conscious investors.

- Companies with clear materiality priorities can leverage the cost-of-inaction argument for the most material climate issues. For a food and beverage company, water—the most important ingredient—served as an ideal starting point, before convincing stakeholders to consider less material issues.

Seek “rewards of action” as the prize

Without a market reward, companies are pressured to prioritize financial performance over sustainability.

– Challenges identified by practitioners

While cost of inaction can be a strong argument, the prize lies in the rewards of action (see Exhibit 2). In BCG and CO2 AI’s 2024 joint carbon emissions survey report, which collected responses from nearly 2,000 companies from 16 industries across 26 countries, over 90% of surveyed companies reported financial gains from decarbonization. 25% of companies saw significant decarbonization benefits equal to or more than 7% of their revenues, for an average net benefit of $200 million a year. A key value driver was reduced operating costs, often through efficiency improvements, waste reduction, streamlined operations, or renewable energy. Additional value drivers included taxation benefits, higher valuations, increased revenues, as well as intangibles (reputation, compliance, supply chain resiliency, talent., etc.).

Blueprints for Success

Repsol has committed to shifting 45% of its capex to renewable sources of energy over the next five years, while AIA has revised its strategy to prioritize investment targets that align with the company’s net zero goals.

We may see markets increasingly favor sustainability leaders. In the 2024 report The Cost of Inaction: A CEO Guide to Navigating Climate Risk it was found that green products can see a 4% to 70% increase in CAGR of sales growth. There is a median upside of 36% in price premiums across 35 consumer packaged goods subcategories.

Blueprints for Success

Using hot or warm water makes up 90% of a washing machine’s energy usage, making it both a significant contributor of CO2 emissions and a lead cost driver for customers. Tide addressed both issues by marketing its Hygienic Clean detergent pods as optimized for cold water. By 2022 product sales had increased by 39%, 1.3 billion loads had been washed in cold water, saving 1 billion kilograms of CO2.

Practices at Starbucks’s Greener Stores, ranging from energy-efficient appliances to standardizing energy use, have helped the company save almost $60 million in annual operating costs in the US, including 30% water savings and 30% energy reduction.

For more details on how to capture climate-based value and examples of success, please refer to “Redesign the Value Chain and Source Strategies” on The Climate Drive.

No-regret foundational moves

- Identify use cases for cost of inaction. Identify two to five specific use cases of applying the cost of inaction to financial decision-making.

- Embed climate in budgeting processes. Incorporate climate considerations into key budget areas like Capex and Opex, focusing on financial, quantitative metrics when possible.

- Engage peers for best practices. Engage with peer companies and cross-industry colleagues to share approaches for climate-financial integration, including strategies for sharing decarbonization costs, assessing cost of climate impacts, and maximizing value.

Learn More

Outline